Kimberley & Pilbara

Kimberley Coast Explorer

March-April 1995

This article was written by Avis Pearce, a South Australian journalist who took part in the trip. The photos were taken by guide Russell Willis.

Note from Russell. Cyclone Chloe made this the most "eventful" of any of our Kimberley Coast trips. But on a trip like this, you have to be prepared to accept whatever the weather might give you.

Driven by Fast Eddy, with swagger and speed rather than care and skill, the tin dinghy juddered to a rasping halt on a semi-submerged rock. The last four of fourteen backpackers decanted and waded ashore to the bank, eighteen kilometres upstream from the mouth of the Berkeley River on the Eastern coastline of the Kimberley region in far north-west Western Australia.

Fast Eddy ruefully examined the propeller of the small outboard, no longer the shape intended by its designer, and waved farewell, as he sculled back to the fishing vessel where the other crew members waited to commence their return journey to Wyndham.

Despite a personal liking for the ambience of the place, I've heard Wyndham described in less polite terms than 'the end of the world'. Certainly it seems to have its fair share of colourful characters, the crew of the fishing boat which had been chartered to bring us to the Berkeley, being no exception.

Besides the happy-go-lucky Fast Eddy, there was captain, Monty, with a salacious leer and a figure that was a definite chance for the 'most-prominent stomach of the year' title, and Hell's Angel look-alike, 'Duck', who with insouciant bravado dived into the Berkeley, the known haunt of salt-water crocs, whenever he wanted to cool off.

The passengers ferried on the eight hour trip from Wyndham were bushwalkers taking part in a five-week epic journey organised and led by Russell Willis of Willis's Walkabouts in Darwin, along the Kimberley coast. The plan was to walk westwards from the Berkeley, across to the King George River and thence to the Drysdale River.

From here a float plane would provide transport back to Lake Kununurra and civilisation after the weeks of isolation in an area with no tracks, few named watercourses, dense vegetation and millions of sandstone rocks. The rocks and formations here have been undisturbed for millions of years, are older than anywhere else in the world and are unreachable except on foot and the only contact with the outside world would be by a radio carried for emergencies.

The three large rivers flow north to south, but are fed by east-west creeks from which water was to be obtained during the journey. Russell had timed the walk for March, to coincide with the end of the Wet season, and the end of torrential rain and cyclones. However, there would still be sufficient water in the creeks for the group's needs. He almost calculated correctly! Water we always had, the only problem being the quantities, due to the inconsiderate advent of Cyclone Chloe, which arrived a week after our departure into the wilderness.

During the first days we explored along the Berkeley, climbed the flat-topped Mount Casuarina and generally acclimatised to the heat and humidity and the weight of packs, which loaded with food and necessities, averaged around 25 kilograms in weight. We soon learned to drink up to ten litres of water a day to cope with the body's needs, to drink early and to drink often and to cool off in any pools or creeks that seemed to be crocodile-free.

Leaving the Berkeley, we struck westwards towards the King George River. We had our first intimation of the imminent approach of Chloe a few day's later, when a clap of thunder followed by lightening too soon afterwards penetrated the mists of sleep. Before we were fully conscious, the heavens had opened and water bucketed down. As we peered out of tents into the dawn light, it became obvious that it had been pouring far longer upstream, as the creek above which we had (as we thought) safely camped, had swollen by an incredible amount. Within half an hour, it was clear that the stream was, in the words of the old Johnny Cash song: 'four feet high and rising', even as we watched.

With a wall of speedily ascending water lapping at our doors, we had no alternative but to grab all belongings, including the tents and race up the muddy ironstone slopes behind the campsite, where we perched in considerable discomfort for three days.

Eventually the weather moderated to a steady drizzle and we decided that we needed to move westwards to the King George River in order to rendezvous with a food drop that would be brought in by Alligator Airways Beaver float plane. Unfortunately, one of the King George's (un-named and normally docile) tributaries had become a raging torrent, sweeping debris ahead of it and making a crossing too dangerous.

For another two days we waited on the banks before launching packs and calculating how far downstream they and swimmers would be swept before reaching a suitable landing area.

After a few more exciting creek crossings, we reached the banks of the King George and established a camp on cliffs high enough to repel the crocodiles we could see below. Russell's radio had refused to function during the Cyclone, but we were now able to make our first contact with Kununurra. The news, however, was not encouraging. The float plane had been damaged, was in the process of being repaired and would be unable to fly and bring our supplies for some time. With some food spoiled by the weather and creek crossings, we were down to our last rations.

Our campsite had stunning views but its nick-name became 'Camp Deprivation' as we waited each day, like members of a Cargo Cult, for the anticipated treasure of food to arrive on the shore. In all, we were without proper nourishment for three days.

Editor's note. A slight exaggeration. We had enough leftovers for a decent meal the first night and really only suffered for two nights.

The effects of the enforced fast on the group were interesting and it was the larger and more macho members who coped less well. Russell, wiry and strong, led exploratory walks each day for those of us who would follow and Geoff and Marianne became heroes when risking the crocs, they went fishing and shared their bounty of four fish with the group one night.

On the fourth morning there was great jubilation and excitement when one of the aeroplane engine noises we had kept hearing, actually turned out to be the real thing and the Beaver circled overhead before making a smooth landing on the King George River below. We scrambled down the cliff and were plucked from the mangroves and ferried by the plane across to the beach on the other side. Food was unloaded and we sat on the sand and wolfed fresh bread, fruit and melting chocolate biscuits that had never tasted so goo

It was surprising how quickly we recovered from the ordeal and after a day's lazing around and eating, were ready to continue upstream to the famous King George Falls.

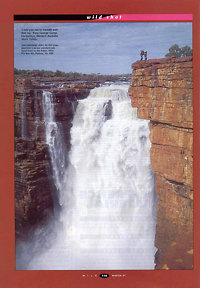

The best thing Chloe and the cyclonic rainfall achieved was to provide torrents that made the Falls utterly spectacular and beyond our best expectations. We spent Easter camped on the cliffs above the Falls watching the fireworks of a tropical storm in the distance and the full moon overhead illuminating the cascading mass of water that roared over the massive twin cataracts, knowing that this was the sight of a lifetime that we were privileged to see.

The photo at the right was taken by Mark Tischler, one of the participants on the trip. It was printed in Wild Magazine.

Reproduced from Wild no. 65 with permission from Wild Publications Pty Ltd.

The adventure continued as we reluctantly left the King George River and trekked overland again to the Drysdale River through a mix of swamps, masses of broken rocks and clumps of palms. We explored the area along the Drysdale, as far south as its junction with the Barton River and discovered a fascinating mix of aboriginal paintings, probably never seen by Europeans before, under many of the overhanging ledges.

As it had been for the whole expedition, the scenery was never less than spectacular, with something new almost every day -- colonies of Flying foxes, pools filled with huge waterlilies, intriguing anthills and highways, magnificent creeks and rapids, views of a coast wild and deserted with white beaches and orange and yellow cliffs studded with massive boulders, twisted rock formations, surveillance by salt water crocodiles who followed us along the River hoping for lunch if we slipped from a rock ledge, carpets of wildflowers brought to blossom by Chloe and so on.

Eventually the float plane arrived, on schedule this time, and we flew to Kununurra in a few hours, enjoying aerial views of the country we had walked for five weeks.

Whenever you travel, it is the unplanned episodes, often perceived as disasters at the time, that become the most memorable and which lift an expedition out of the ordinary. So it is no surprise that out of a remarkable five week odyssey, it is especially Cyclone Chloe, Camp Deprivation and that Easter at the King George Falls that dominate my memories. As John Steinbeck wrote: ' A journey is a person in itself. ..We find after years of struggle that we do not take a trip; a trip takes us'.

See more photos in the Kimberley Coast 1995 Gallery

More Kimberley Coast explorer trip information

share

share